I’ve been in love with the theatre since I was 12 years old. I spent my pubescent years with copies of Macbeth and Angels in America and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in constant rotation. Until finishing school, there was never any question in my mind where I would spend my life and career.

The gradual melting away of my childhood dreams of the stage began when, at 18, enrolled in America’s oldest drama conservatory in Manhattan, the casting announcements for our first year finals were posted. Eagerly dragging my finger down the list of plays, one of which was Wendy Wasserstein’s love letter to second-wave feminism, ‘Uncommon Women and Others’, I found my name nestled sadly near the bottom of the cast list for a self-indulgent modern drama called ‘Boy’s Life’. The name of the character to the left of my own was simply ‘Girl’. I would later discover that the director’s choice to cast me as this sad, nameless, stereotype of a woman was made for one reason alone: I was quiet, reserved, and uncomfortable in my skin. As far as the programme directors at this historical institution were concerned, if I had any hope of working as an actress, I needed to get comfortable wearing lingerie onstage.

So ended my first and last year in American drama school; draped in translucent silk and running my mouth over the body of a man I could barely stand to share a room with, trying my best to exude confidence in front of a room full of (mostly male) authority figures. It didn’t work. I wasn’t invited back.

The gradual melting away of my childhood dreams of the stage began when, at 18, enrolled in America’s oldest drama conservatory in Manhattan, the casting announcements for our first year finals were posted. Eagerly dragging my finger down the list of plays, one of which was Wendy Wasserstein’s love letter to second-wave feminism, ‘Uncommon Women and Others’, I found my name nestled sadly near the bottom of the cast list for a self-indulgent modern drama called ‘Boy’s Life’. The name of the character to the left of my own was simply ‘Girl’. I would later discover that the director’s choice to cast me as this sad, nameless, stereotype of a woman was made for one reason alone: I was quiet, reserved, and uncomfortable in my skin. As far as the programme directors at this historical institution were concerned, if I had any hope of working as an actress, I needed to get comfortable wearing lingerie onstage.

So ended my first and last year in American drama school; draped in translucent silk and running my mouth over the body of a man I could barely stand to share a room with, trying my best to exude confidence in front of a room full of (mostly male) authority figures. It didn’t work. I wasn’t invited back.

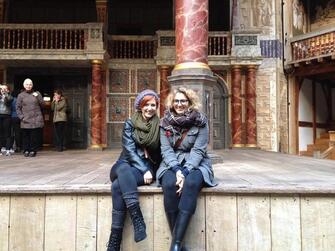

Maria & Erica at LAMDA

Maria & Erica at LAMDA

I spent the majority of my 20s trying to carve out a space for myself in an industry that didn’t seem to want me. Though I didn’t realise it at the time, my sour experience at drama school had planted a seed in my mind that I wouldn’t have the opportunity to nourish until nearly a decade later.

In 2014, I left my beloved New York behind and began a year of intensive study at LAMDA. It was a very expensive last-ditch attempt to rekindle a love of performance. I told myself that, if at the end of my year there I didn’t feel renewed, I would officially close the book on that chapter of my life and seek out a career in museum education or publishing or literally anything that didn’t require $300 biannual headshots. Although my studies there were invaluable, the most important thing I gained from my time there was a fast friendship with a spunky Canadian opera singer named Erica Martin. She was fresh from the opera world and learning for the first time what the casting limitations are for young women hoping to eke out a living in theatre. Although the roles we were given in LAMDA’s academic setting were meaty and challenging and deeply satisfying, we grew increasingly aware as the year rolled on that those roles were likely to dry up for us as soon as we graduated. In preparing audition pieces, we were consistently told to be sure to stick to our gender. This struck me as odd and unnecessary. Why? What about Richard II’s dying speech is so intrinsically male it should be unavailable to me, even for auditions? Why, when our instructors were consistently casting us in male roles out of sheer necessity, shouldn’t we be working toward those roles going forward in our careers?

In 2014, I left my beloved New York behind and began a year of intensive study at LAMDA. It was a very expensive last-ditch attempt to rekindle a love of performance. I told myself that, if at the end of my year there I didn’t feel renewed, I would officially close the book on that chapter of my life and seek out a career in museum education or publishing or literally anything that didn’t require $300 biannual headshots. Although my studies there were invaluable, the most important thing I gained from my time there was a fast friendship with a spunky Canadian opera singer named Erica Martin. She was fresh from the opera world and learning for the first time what the casting limitations are for young women hoping to eke out a living in theatre. Although the roles we were given in LAMDA’s academic setting were meaty and challenging and deeply satisfying, we grew increasingly aware as the year rolled on that those roles were likely to dry up for us as soon as we graduated. In preparing audition pieces, we were consistently told to be sure to stick to our gender. This struck me as odd and unnecessary. Why? What about Richard II’s dying speech is so intrinsically male it should be unavailable to me, even for auditions? Why, when our instructors were consistently casting us in male roles out of sheer necessity, shouldn’t we be working toward those roles going forward in our careers?

A production photo from Ajax

A production photo from Ajax

Erica and I spent long nights in our little Chiswick flat discussing the incredible imbalance of gender in the pieces we loved most. We worked together on a thesis addressing female voice types in archetypal roles. For our final production, in stark contrast to my experience a decade earlier, we were given the roles of Brutus and Caesar in an all-female production of my favourite of Shakespeare’s histories. In addition to the myriad other joys of that experience (a blog post on its own), the audience response was consistent and reaffirming: by removing the Old White Man tradition of the piece, we allowed the story and relationships to shine through.

This experience solidified for us what we already knew on some level we wanted to do. Since we had always wanted to play these roles, we would simply do it, and drag as many talented women along with us as possible. We sat in corners at Foyles, scouring through classical plays, making lists of possibilities. We spent hours on skype from opposite sides of an ocean. Finally we settled on what would be our first production.

Ajax was not an obvious choice. Discussing our plans in rooms full of performers tended to elicit strange looks. We had chosen what is possibly the most distinctly masculine play in the Greek canon to kick off an all-female production company. However, despite our second thoughts, our casting notice was met with a flood of women hoping to participate. We learned quickly that we are not the only women in this industry craving challenging work. Not only that, but audiences want to see it.

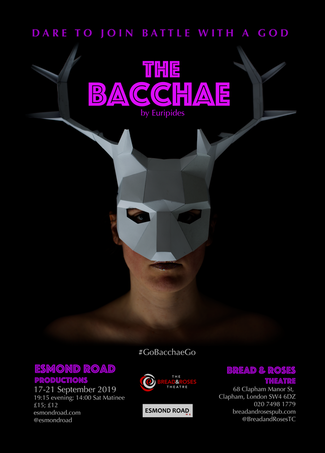

Euripides’ classic tragedy, The Bacchae, seems like the logical next step for us. We are able to take what we learned from Ajaxabout the flexibility of gender in the Greeks and add to it a colourful, modern flair. Erica’s original music, a well-loved feature of our work, is given a tongue-in-cheek contemporary twist that her fans will undoubtedly love. We brought in five new female and non-binary performers (two of whom had auditioned for Ajax, as well) and a young female lighting designer fresh out of school. We are incredibly optimistic about the response to this production, and cannot wait to take our hard work to the public.

It’s true, in many ways, that progress has been made for female-identifying, gender fluid, and non-binary artists in recent years. In other ways, though, we’ve taken steps back. Female roles have, remarkably, decreased in film in the last decade. The age of #MeToo has exposed a great deal of the gender-related toxicity and abuse in the entertainment industry. It is the responsibility of every artist to confront these inequalities in whatever way they can. We are a small fringe company doing old plays for audiences of 40 people at a time, our individual power is limited. Our dream is that, in the coming years, we will become but one of many, many little companies working toward the same goal. We hope, sooner rather than later, to see women and non-binary artists covering every stage, filling every soundbooth, climbing on every lighting rig in London. Sound good? We think so, too.

#GoBacchaeGo

The Bacchae runs 17 - 21 September 2019 at The Bread & Roses Theatre

BOOK NOW

This experience solidified for us what we already knew on some level we wanted to do. Since we had always wanted to play these roles, we would simply do it, and drag as many talented women along with us as possible. We sat in corners at Foyles, scouring through classical plays, making lists of possibilities. We spent hours on skype from opposite sides of an ocean. Finally we settled on what would be our first production.

Ajax was not an obvious choice. Discussing our plans in rooms full of performers tended to elicit strange looks. We had chosen what is possibly the most distinctly masculine play in the Greek canon to kick off an all-female production company. However, despite our second thoughts, our casting notice was met with a flood of women hoping to participate. We learned quickly that we are not the only women in this industry craving challenging work. Not only that, but audiences want to see it.

Euripides’ classic tragedy, The Bacchae, seems like the logical next step for us. We are able to take what we learned from Ajaxabout the flexibility of gender in the Greeks and add to it a colourful, modern flair. Erica’s original music, a well-loved feature of our work, is given a tongue-in-cheek contemporary twist that her fans will undoubtedly love. We brought in five new female and non-binary performers (two of whom had auditioned for Ajax, as well) and a young female lighting designer fresh out of school. We are incredibly optimistic about the response to this production, and cannot wait to take our hard work to the public.

It’s true, in many ways, that progress has been made for female-identifying, gender fluid, and non-binary artists in recent years. In other ways, though, we’ve taken steps back. Female roles have, remarkably, decreased in film in the last decade. The age of #MeToo has exposed a great deal of the gender-related toxicity and abuse in the entertainment industry. It is the responsibility of every artist to confront these inequalities in whatever way they can. We are a small fringe company doing old plays for audiences of 40 people at a time, our individual power is limited. Our dream is that, in the coming years, we will become but one of many, many little companies working toward the same goal. We hope, sooner rather than later, to see women and non-binary artists covering every stage, filling every soundbooth, climbing on every lighting rig in London. Sound good? We think so, too.

#GoBacchaeGo

The Bacchae runs 17 - 21 September 2019 at The Bread & Roses Theatre

BOOK NOW

RSS Feed

RSS Feed